Class blog for PAT 452/552 – Interactive Media Design II – Department of Performing Arts Technology

Saturday, January 30, 2016

Thinking about strings

I found this instrument very fascinating. Kevin have you seen this?

IT SOUNDS BEAUTIFUL.

I think what I enjoy so much about it is the acoustic nature of it. But I do wonder what kind of sounds you could synthesize or create from amplifying the actual string resonance.

Such an interesting instrument. Wondering what the other pedal does, and exactly how the strings are excited specifically.

Initial Design Finished and ready for printing, some thoughts on sound...

One of my favorite things about this semester is finally having the opportunity (and the reason) to wrap my head around Computer Aided Design. While I could have used it before in many instances, its use was never imperative because I didn't have the concurrent Computer Aided Manufacturing capabilities...this has changed now that we have generous access to multiple stereolithographs, or as they are more prosaically and less poetically called, 3D printers.

While we have access to the top of the line design software in the Labs at Michigan, specifically the industry standard Solidworks, I instead decided to start working with the Autodesk Fusion360 software. This was mostly so that I, because I'm a commuting student, didn't need to be tied to the computer labs and I could work on my designs at home. Another reason was that Fusion360 has a super generous three years free student license and much more affordable rates after that. I didn't want to dive too deep into Solidworks, fall in love, and then not get to use it after graduation because of the $3500+ license fee.

I have found Fusion360 to have a very easy, almost curated, learning curve. It comes with a huge host of 'in application' hands on tutorials and a comprehensive online documentation. It also automatically works in the cloud, making sharing and backups as easy as using social media. So, all that being said, here is what I've come up with so far...

After our last in class review, I've tried to do some thinking about what 'sound' the bucky would be tied to. This wasn't my focus so much in my first conception, I was more attentive to various design concerns. I wanted several factors; something that could use as many affordances as the shoulder-arm-elbow-wrist-finger combination allows (impossible to get them all, our hands are amazing devices!), something that would invite touch, and something that would make understandable musical changes right out of the box while allowing for creative growth. As I think about sound, I'm still drawn to thinking about 'What are the controlled parameters?' as much as I'm thinking about a particular synthesis patch. For instance, combining data from the two sensors, I can get Y-axis velocity data from the ITU and get distance data from the proximity sensor. This could lead to an interaction that has a metaphor in the pizz to arco range on a string instrument. The ITU data would set the initial attack time of the sound with faster movement meaning shorter attack, and the depth of the plunger would set the initial attack level, deeper being louder. So a fast descent of the Bucky with a shallow compression of the plunger would be a quiet pizzicato; light compression of the plunger with almost no Y-axis movement would be a soft arco; fast Y-axis with deep compression would be accented sustained attack, etc. This, of course does not have to be tied to volume envelope, it could be transferred to the filter, to LFO, whatever we usually would tie to an ADSR in the modular synth paradigm.

While we have access to the top of the line design software in the Labs at Michigan, specifically the industry standard Solidworks, I instead decided to start working with the Autodesk Fusion360 software. This was mostly so that I, because I'm a commuting student, didn't need to be tied to the computer labs and I could work on my designs at home. Another reason was that Fusion360 has a super generous three years free student license and much more affordable rates after that. I didn't want to dive too deep into Solidworks, fall in love, and then not get to use it after graduation because of the $3500+ license fee.

I have found Fusion360 to have a very easy, almost curated, learning curve. It comes with a huge host of 'in application' hands on tutorials and a comprehensive online documentation. It also automatically works in the cloud, making sharing and backups as easy as using social media. So, all that being said, here is what I've come up with so far...

The top compartment is made to hold all of the electronics, with a proximity sensor mounted on the bottom of the removable disk and the Inertial Tracking Unit mounted on the top. As both of my sensors are i2c there will be a minimal amount of wiring in the housing as I believe I can daisy chain power and data, hopefully coming out of the device with a clean four wire + shield cable. Later on I want to look at modifying the electronics to include Bluetooth, but that's for an iteration far in the future. I do not consider this the finished geometry for the project, this is more proof of concept, and it was designed with the Cube2 printers in mind, which only have an effective print surface of around 4.5". While I believe the height, at around 4.5" assembled and at rest is about right for the scale of the human hand, I would like to extend the ring out another two inches or so. Now that we have access to the department printers, this will be in my next iteration because I believe there is around an eight inch print surface.

The new departmental printers! I've been working with John Granzow a bit in the setup and calibration of the two printers, and we've done some trial runs of simple parts. There is a lot of combinations of variables that must be taken into account, between the material, nozzle, heat, travel speed etc, but they should be up and running in a little while. Here's some vid of a test run. I love the music of the stepper motors!

Friday, January 29, 2016

The Alienation of Ornamental Interaction

In reading Johnston's "Designing and evaluating virtual musical instruments: facilitating conversational user interaction" for our discussion on Thursday, I was very glad for the distinction he made between instrumental and ornamental interaction. Applying it to my own project of the income inequality data-driven percussion, it's clear to me that my current design encourages (or even mandates) an ornamental mode of interaction. Currently, income-inequality data structures the mapping of percussive hit to audio processing, with the mapping changing over the course of the composition. What struck me most about this realization was that this mode of interaction would may cause the user to feel some kind of alienation by my design, as studied by Johnston's qualitative experiment. For example Musician J is quoted as saying: "If you want a feeling of domination and alienation, that's certainly there with that one. I'm not being sarcastic. If you want the feeling that the machine actually is the dominant thing then that creates it quite strongly...It's very strong, the feeling of alienation makes me uneasy. And if it's in a different section of long piece then it certainly creates tension."

I am going and back and forth with how directly I want to elicit or not elicit this kind of emotional response from the user. On the one hand, a reading of the concept of the piece would be reinforced by a feeling of alienation, which mirrors the middle class's feeling of alienation from the wealth of American society. On the other hand, I generally don't like art works that direct user responses so explicitly, and that is something worth interrogating. If an art work has such a dictatorial approach, a subject might find it less engaging, because the work of figuring out the metaphor/message would already be given. Furthermore, in such a political work, I'm worried about reducing a very politically charged topic to trivial mappings. What's more interesting to me is the possibility of creating a space that suggests a feeling of alienation, that then triggers the user to reflect and explore where that alienation occurs in their lives away from my musical interface- in other words, to put the pieces together for themselves, and in a politically productive fashion. That will be quite a hard challenge, but no one ever said this project would be easy!

I am going and back and forth with how directly I want to elicit or not elicit this kind of emotional response from the user. On the one hand, a reading of the concept of the piece would be reinforced by a feeling of alienation, which mirrors the middle class's feeling of alienation from the wealth of American society. On the other hand, I generally don't like art works that direct user responses so explicitly, and that is something worth interrogating. If an art work has such a dictatorial approach, a subject might find it less engaging, because the work of figuring out the metaphor/message would already be given. Furthermore, in such a political work, I'm worried about reducing a very politically charged topic to trivial mappings. What's more interesting to me is the possibility of creating a space that suggests a feeling of alienation, that then triggers the user to reflect and explore where that alienation occurs in their lives away from my musical interface- in other words, to put the pieces together for themselves, and in a politically productive fashion. That will be quite a hard challenge, but no one ever said this project would be easy!

Thursday, January 28, 2016

Initial ideas...and some problems.

As we move along this semester, I thought I'd present my current working idea and some of the issues that I'm working on resolving. So I was initially trying to work on a cube-shaped instrument (kind of like a Rubik's cube) that allowed me to take its individual cubes and pull them out and orient them around its axis' to control sound. However, after finding some not-so-great cube-shaped instruments and not being able to solve how to measure the distance from the main cube, I have totally abandoned that idea.

Instead, I was drawn to these hanging lights that you always seem to see in super hip cafe's and bars.

I was also perusing my favorite design site and stumbled across Phillip K. Smith III's "Double Truth", which explores shadow and light as it falls on objects. Here's a selection from a gallery showing:

So where am I headed from here? I haven't done a whole lot with photoresistors, so I'm experimenting with how dynamic they can be. I also plan on experimenting with different kinds of lights at different wattages. I'm also looking at how to best hang these lights from a frame, and what kind of weight the frame would need to be able to carry depending on what light I go with.

Aaaand...that's the plan!

Instead, I was drawn to these hanging lights that you always seem to see in super hip cafe's and bars.

I was also perusing my favorite design site and stumbled across Phillip K. Smith III's "Double Truth", which explores shadow and light as it falls on objects. Here's a selection from a gallery showing:

The combination of the hanging lights and this play of shadow and light made me think of a system that explores the interplay of shadow and light. I envision an apparatus that looks something like this:

I imagine a series of lights or lamps hanging from a frame shining down photoresistors. After some thought of how to visually engage and show the interaction more, I'm drawn to the idea of mounting the photoresistors on geometric shapes (akin to the random shapes on the wall in Smith's work). I toyed with the idea of using random old objects, but if I use already existing objects, I'll impose a visual/aesthetic/sonic/contextual identity on the system I create. If I use "random" geometric shapes (which I'm thinking of 3D printing), I'll have more control over the shadows I create without imposing an identity on the work--I'm thinking it'll bring more focus to this idea of shadow and light. Maybe if I create cavities for cylinders with varying "tops" to put underneath the lights that I can rotate and control the shadows, but not necessarily the position of these shapes. Hmm..things to think about.

As for the lights themselves, I have a two light system in mind (with 4 lights, so two of each). One set of lights will simply hang from the frame, and I'll be able to make them swing and create continuously changing light conditions. The other lights I'll be able to bend like desk lamps and have greater control over what those lights are doing and what shadows they create.

Peter suggested that I find a way to actuate the lights so that I have more control over when each light is on. I really, really like that idea, but it'll definitely take more research than I've done in that department. I want to be able to tap a light to turn it on and then tap it again to turn it off.

I really like this whole idea because not only do I have a sonic identity that I can hear in my head, but there's also a learning aspect to it. It'll take me (and whoever else chooses to engage in this system) time to learn how the shadows, lights and varying placements of the photoresistors will influence the sound. There'll also be a learning aspect whenever the system is placed somewhere new--I'll have to adapt to the new lighting conditions of the room.

So where am I headed from here? I haven't done a whole lot with photoresistors, so I'm experimenting with how dynamic they can be. I also plan on experimenting with different kinds of lights at different wattages. I'm also looking at how to best hang these lights from a frame, and what kind of weight the frame would need to be able to carry depending on what light I go with.

Aaaand...that's the plan!

Wednesday, January 27, 2016

More bowing inspiration: The nail violin

Tuesday, January 26, 2016

String Potentiometers Revisited

Last year I spent a lot of time researching GameTrak string potentiometer technology and ways to use it.

Although I'm not planning on using string potentiometers again this semester, I've gone back to researching GameTraks again for a redesign of the String Accordion. I've specifically been working on finding alternative sources for my string potentiometer needs, thinking about building them out of easily attainable parts rather than fishing them out of GameTraks.

A new GameTrak design came out in 2006 just before the company was bought out, right before the Wii revolution of wireless motion sensing remotes. The string based system was eventually dropped for a Wiimote clone that was obviously unsuccessful. Unfortunately, the last tech update to GameTrak before it jumped over to wireless was a really nice step up from the original.

This was a brilliant change in design for GameTrak. Instead of having the plastic flange for the PCB to sit on, the new design had it screwed directly into the spring enclosure. It boasts a smaller footprint and easily accessible wires via a smaller, new PCB by the string length potentiometer. It's everything I'm looking for in a string potentiometer system, but they only ran a short production in the UK in 2006. UGH.

All that's left is here: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Mad-Catz-Gametrak-Controller-PS2/dp/B000B0N448

Even with that, I can't guarantee that those are the right type. The new GameTraks look like they're lumped in with the old ones, and I'd hate to pay premium shipping to get the same old GameTraks I already have.

In researching ways to build my own GameTrak system, I've found that it's fairly simple to measure string length. Quadrature on a tape measure type system would do the trick, but the real tough part is measuring the XY position like the GameTrak does. I've scoured the internet and I still haven't found a viable alternative.

I'm considering an attempt to get in contact with the engineer accredited to this design. I wonder if he knows how useful his contraption is to the design world right now?

Although I'm not planning on using string potentiometers again this semester, I've gone back to researching GameTraks again for a redesign of the String Accordion. I've specifically been working on finding alternative sources for my string potentiometer needs, thinking about building them out of easily attainable parts rather than fishing them out of GameTraks.

A new GameTrak design came out in 2006 just before the company was bought out, right before the Wii revolution of wireless motion sensing remotes. The string based system was eventually dropped for a Wiimote clone that was obviously unsuccessful. Unfortunately, the last tech update to GameTrak before it jumped over to wireless was a really nice step up from the original.

This was a brilliant change in design for GameTrak. Instead of having the plastic flange for the PCB to sit on, the new design had it screwed directly into the spring enclosure. It boasts a smaller footprint and easily accessible wires via a smaller, new PCB by the string length potentiometer. It's everything I'm looking for in a string potentiometer system, but they only ran a short production in the UK in 2006. UGH.

All that's left is here: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Mad-Catz-Gametrak-Controller-PS2/dp/B000B0N448

Even with that, I can't guarantee that those are the right type. The new GameTraks look like they're lumped in with the old ones, and I'd hate to pay premium shipping to get the same old GameTraks I already have.

In researching ways to build my own GameTrak system, I've found that it's fairly simple to measure string length. Quadrature on a tape measure type system would do the trick, but the real tough part is measuring the XY position like the GameTrak does. I've scoured the internet and I still haven't found a viable alternative.

I'm considering an attempt to get in contact with the engineer accredited to this design. I wonder if he knows how useful his contraption is to the design world right now?

Saturday, January 23, 2016

Friday, January 22, 2016

Whoa Radio Drum Reboot at NAMM...Nice Stuff from former Trinity College Dublin....

Not really a radio drum per se, but the same outcome.

http://www.synthtopia.com/content/2016/01/22/aerodrums-intros-virtual-reality-drum-set-for-oculus-rift/

http://www.synthtopia.com/content/2016/01/22/aerodrums-intros-virtual-reality-drum-set-for-oculus-rift/

The Data-Driven DJ and the Dangers of Style

I'm focusing my design towards the sketch of a data-driven percussive instrument that I presented in class a week ago, and in my research I've come across an interesting data-driven musician I'd like to share with you. He goes by the name the Data-Driven DJ, real name Brian Foo, and is a conceptual artist/programmer. He has quite a few projects already, each focusing on a different data set, including one on income inequality along a NYC subway line. Click to watch

His visualizations are beautiful, and well synchronized with the presentation of data. However, I find that his musical mappings vary from imaginative to not interesting, and though he admits that he has formal musical training and is getting better with each project. He intentionally restricts himself to a sound world within each project (though) and often relies on musical gestures and sounds for his mappings that together connote a distinct and pre-existing style (popular music, or in the case above, Steve Reich). While this might make his work aurally accessible, the reliance on pre-existing styles makes his work predictable across the span of each composition, and reduces the drama within each data-set. E.g. in the subway project above, the sounds signifying areas with high median income aren't really that different from lower median income areas. If his purpose was to orient the listener towards the sharp contours of the dataset, I think relying on a pre-existing style took away the potential for shock at any particular datapoint.

I think his work will be very useful for prompting questions about the aptness of musical mappings to data, and most importantly for his very generous documentation, which he compiles for every project here. He uses the programming language CHUCK for mapping audio parameters, and I think I would like to explore how CHUCK might compare to MAX-MSP for my purposes. To close, I'd like to present my favorite project of his so far, documenting the travel of refugees from a UNHCR dataset (I think the musical mappings are more mature and nuanced in this one) Click to watch

His visualizations are beautiful, and well synchronized with the presentation of data. However, I find that his musical mappings vary from imaginative to not interesting, and though he admits that he has formal musical training and is getting better with each project. He intentionally restricts himself to a sound world within each project (though) and often relies on musical gestures and sounds for his mappings that together connote a distinct and pre-existing style (popular music, or in the case above, Steve Reich). While this might make his work aurally accessible, the reliance on pre-existing styles makes his work predictable across the span of each composition, and reduces the drama within each data-set. E.g. in the subway project above, the sounds signifying areas with high median income aren't really that different from lower median income areas. If his purpose was to orient the listener towards the sharp contours of the dataset, I think relying on a pre-existing style took away the potential for shock at any particular datapoint.

I think his work will be very useful for prompting questions about the aptness of musical mappings to data, and most importantly for his very generous documentation, which he compiles for every project here. He uses the programming language CHUCK for mapping audio parameters, and I think I would like to explore how CHUCK might compare to MAX-MSP for my purposes. To close, I'd like to present my favorite project of his so far, documenting the travel of refugees from a UNHCR dataset (I think the musical mappings are more mature and nuanced in this one) Click to watch

Design Themes/Idea Board

Discussion in class this week, as well as the readings, had several common themes. One of the most important, at least for me, is the exploration of the intuitiveness of the interface. Interface is the keyword here; it's important to point out that I do not mean the interface in our normal usage, as in the total object from handle to USB plug, but the actual transducer to skin contact, the margin where the human meets the machine. In order for the instrument to have an emotional resonance for the performer attention must be paid to whether or not it has a physical resonance, whether or not it invites or repels the actual touch of the performer.

For whatever reason, when I'm thinking about this level of the interface my gold standard, or at least the traditional instrument my mind defaults to, is the cello. Never having done much with cello other than sit down with it and try and saw out a couple of sensible tones, I'm still drawn to its performance practice and it's particular characteristics. To start with, you don't just hold the cello, you fully embrace it with your entire body; arms, legs, even neck and head curl around the instrument in an intimacy usually reserved for objects of our affection in more private settings. As it vibrates, you don't just hear it, you don't just feel it with your hands; it sings outwards from your core to your extremities. I find the neck size to be perfectly sized for human hands, not the crowding of the violin or guitar neck, and not the cumbersome lengths of the double bass. The back of the neck as it rests in the crook of the thumb is smooth and invites movement, and when you let it go it rests against your neck and shoulder awaiting the next passage without any need for further physical engagement. The right hand is held at a very natural position for the human animal, near it's resting place. When actively bowing it's a smooth easy motion for shoulder arms and hands. Even when the cellist is digging in for a harsh attack, the mechanics of the posture work to their advantage; the bow pushes inward and the body pushes outward, creating a compression like mechanic that has a metaphor in the ki-hup of martial artists, a direct physical analog of the audible result.

I, of course, am not going to reinvent the cello. Little outside my current level of ability and a touch outside the scope of the class. But thinking about this did change my initial thoughts on the human/machine connection. At first I was going to go with the ubiquitous smooth plastic of most outboard music gear, sort of the inescapable iAesthetic. I was going to mix that with a little Jet Age/ Mod/ Star Trek styling and come up with a piece of equipment you'd find sitting on Spock's bedstand. Here are a few pictures from that aesthetic:

Mechanically, the shape fits right in to the device idea that I'm currently following. The curves are also very inviting, but something about the shiny plastic declines engagement, it's antiseptic and a little too formal, institutional. It was intimate in Barbarella, but that's about it. So I like the shape, but not the material. This is where thinking about the cello started, and I wondered how people are combining wood and electronics. It was quite common when I was young, even televisions came wrapped in wood with fine scrollwork and expensive finishes, but that was back when a television was huge, a significant investment, and doubled as a table in your living room. We haven't seen much of that in the past thirty years, especially as electronics have become cheaper, smaller and disposable. Well, it turns out that aesthetic is returning; perhaps as people are realizing a new form of intimacy with their devices they want a more comfortable material to hold, and to hold against their bodies and to have in their homes. Here's some things I found:

For me, the wood definitely invites touch, and it's handsome to boot. I think I'll use a metal armature for the structure of the device, but find some way to work wood into the touchable surfaces of the interface, similar to the last picture which is a form of computer mouse you hold in your hand.

Another design aspect I have to mention is the influence of sculpture Kenneth Snelson and architect Buckminster Fuller and their idea of the tensigrity. Tensigrity is the name that Fuller came up with for Snelson's sculptures, it is a combination of Tension and Integrity, and has the poetic description of 'Islands of Compression in a Sea of Tension'. Tensigrity follows Fuller's earlier work on the concept of the Dymaxion system, Dymaxion being another Fullerism that means Dynamic Maximum Tension. Fuller first found fame in his Dymaxion Car and Dymaxion House (of which the only remaining one now resides in the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, MI) Fuller went on to invent the geodesic dome and spent the remainder of his life evangelizing on the idea that the triangle was the fundamental geometry of the universe and how much he hated Pi. After his death, a carbon molecule was created based on his principles and named after him, the Fullerene. It is the basic component of carbon nanotubes, themselves a key component in nano-manufacturing. Here's some pictures of Snelson and Bucky influenced stuff:

For whatever reason, when I'm thinking about this level of the interface my gold standard, or at least the traditional instrument my mind defaults to, is the cello. Never having done much with cello other than sit down with it and try and saw out a couple of sensible tones, I'm still drawn to its performance practice and it's particular characteristics. To start with, you don't just hold the cello, you fully embrace it with your entire body; arms, legs, even neck and head curl around the instrument in an intimacy usually reserved for objects of our affection in more private settings. As it vibrates, you don't just hear it, you don't just feel it with your hands; it sings outwards from your core to your extremities. I find the neck size to be perfectly sized for human hands, not the crowding of the violin or guitar neck, and not the cumbersome lengths of the double bass. The back of the neck as it rests in the crook of the thumb is smooth and invites movement, and when you let it go it rests against your neck and shoulder awaiting the next passage without any need for further physical engagement. The right hand is held at a very natural position for the human animal, near it's resting place. When actively bowing it's a smooth easy motion for shoulder arms and hands. Even when the cellist is digging in for a harsh attack, the mechanics of the posture work to their advantage; the bow pushes inward and the body pushes outward, creating a compression like mechanic that has a metaphor in the ki-hup of martial artists, a direct physical analog of the audible result.

I, of course, am not going to reinvent the cello. Little outside my current level of ability and a touch outside the scope of the class. But thinking about this did change my initial thoughts on the human/machine connection. At first I was going to go with the ubiquitous smooth plastic of most outboard music gear, sort of the inescapable iAesthetic. I was going to mix that with a little Jet Age/ Mod/ Star Trek styling and come up with a piece of equipment you'd find sitting on Spock's bedstand. Here are a few pictures from that aesthetic:

Mechanically, the shape fits right in to the device idea that I'm currently following. The curves are also very inviting, but something about the shiny plastic declines engagement, it's antiseptic and a little too formal, institutional. It was intimate in Barbarella, but that's about it. So I like the shape, but not the material. This is where thinking about the cello started, and I wondered how people are combining wood and electronics. It was quite common when I was young, even televisions came wrapped in wood with fine scrollwork and expensive finishes, but that was back when a television was huge, a significant investment, and doubled as a table in your living room. We haven't seen much of that in the past thirty years, especially as electronics have become cheaper, smaller and disposable. Well, it turns out that aesthetic is returning; perhaps as people are realizing a new form of intimacy with their devices they want a more comfortable material to hold, and to hold against their bodies and to have in their homes. Here's some things I found:

For me, the wood definitely invites touch, and it's handsome to boot. I think I'll use a metal armature for the structure of the device, but find some way to work wood into the touchable surfaces of the interface, similar to the last picture which is a form of computer mouse you hold in your hand.

Another design aspect I have to mention is the influence of sculpture Kenneth Snelson and architect Buckminster Fuller and their idea of the tensigrity. Tensigrity is the name that Fuller came up with for Snelson's sculptures, it is a combination of Tension and Integrity, and has the poetic description of 'Islands of Compression in a Sea of Tension'. Tensigrity follows Fuller's earlier work on the concept of the Dymaxion system, Dymaxion being another Fullerism that means Dynamic Maximum Tension. Fuller first found fame in his Dymaxion Car and Dymaxion House (of which the only remaining one now resides in the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, MI) Fuller went on to invent the geodesic dome and spent the remainder of his life evangelizing on the idea that the triangle was the fundamental geometry of the universe and how much he hated Pi. After his death, a carbon molecule was created based on his principles and named after him, the Fullerene. It is the basic component of carbon nanotubes, themselves a key component in nano-manufacturing. Here's some pictures of Snelson and Bucky influenced stuff:

Thursday, January 21, 2016

Building Blocks

In a number of my initial designs, I kept coming back to this idea of a cube. I've now since fixated on that same cube and have been thinking about how you can break down or build a cube by amalgamating more cubes, like a Rubik's cube. Although I have a pretty solid conceptual idea (which I'll share once it's a little more fleshed out), I've felt pretty stuck in the last week or so, and I'm not sure how to develop my idea further. So, I've been looking at my favorite design websites, as well as some random bookmarks trying to find inspiration, when I stumbled upon this, an old bookmark from years ago.

It's formatted like a basic Internet article, with the clickbait title and itemized list. But the idea of repurposing old shipping containers for home design reminded me of the project we are embarking on. Although we're not attempting something on the scale of building a new home, we are creating something new. Hopefully, anyway. These people have taken a shipping container (or multiple), something with a certain identity and totally changing that perspective. Here are just a couple of my favorite redesigns.

So while the idea of a shipping container is still in tact, they've totally transformed its use.

I decided to look up shipping containers on my favorite design site, and found this project, a building designed in Korea. This quote from the opening stuck with me:

Anyway, all of this has me rethinking the cube. Well. Not rethinking it, because I still feel pretty attached to that idea, but just thinking about ways that the cube can move and grow and breathe and exist. Which is in turn influencing the way I'm imaging its sound design (particularly if I take influence from these shipping containers).

My thoughts still have a lot of percolating to do, but things are definitely looking up compared to where they were earlier this week!

It's formatted like a basic Internet article, with the clickbait title and itemized list. But the idea of repurposing old shipping containers for home design reminded me of the project we are embarking on. Although we're not attempting something on the scale of building a new home, we are creating something new. Hopefully, anyway. These people have taken a shipping container (or multiple), something with a certain identity and totally changing that perspective. Here are just a couple of my favorite redesigns.

So while the idea of a shipping container is still in tact, they've totally transformed its use.

I decided to look up shipping containers on my favorite design site, and found this project, a building designed in Korea. This quote from the opening stuck with me:

"Constructed by 28 ISO cargo containers which were brilliantly and thoughtfully stacked as if a young child was playing and placing building blocks one on top of another trying to construct a building."

Now we've added this new context in terms of the cube, and how it's been used. And yeah, shipping containers aren't cubes, but they're pretty close. You could argue that they're comprised of cubes.

My thoughts still have a lot of percolating to do, but things are definitely looking up compared to where they were earlier this week!

Tuesday, January 19, 2016

The MICKEYPHON

I was checking out some music tech sites for instrument design inspiration and I stumbled upon an interactive sculpture made by Polish design firm panGenerator. The MICKEYPHON is inspired by Mickey Mouse and has an aesthetic that is definitely geared towards children. The device is paired with a Max MSP patch and uses hidden-microphones to record the sounds of the gallery and rhythmically chop and sequence them to a predefined tempo. The patch also uses localization techniques to turn the head towards the loudest sound source. Inside the MICKEYPHON is an LED matrix that displays hints on the looper's position and when the head is recording.

While this is more of a toy than an instrument, I think that panGenerator succeed in building a very interactive experience that calls on both physical and musical emotions. In my opinion, the MICKEYPHON's most interactive element is the process of localizing the loudest sound source and turning it's head towards it. I found this to be a very human response for a machine to have. It not only informs the audience member that they have been detected, but it encourages them to produce sounds that will then be intertwined with other's later. I could easily see this kind of "interactive sculpture" being used in a school or hospital setting.

MICKEYPHON - kinetic av sculpture created for Disney from ◥ panGenerator on Vimeo.

While this is more of a toy than an instrument, I think that panGenerator succeed in building a very interactive experience that calls on both physical and musical emotions. In my opinion, the MICKEYPHON's most interactive element is the process of localizing the loudest sound source and turning it's head towards it. I found this to be a very human response for a machine to have. It not only informs the audience member that they have been detected, but it encourages them to produce sounds that will then be intertwined with other's later. I could easily see this kind of "interactive sculpture" being used in a school or hospital setting.

MICKEYPHON - kinetic av sculpture created for Disney from ◥ panGenerator on Vimeo.

Monday, January 18, 2016

Designing an instrument that reflects changing environments

An instrument sounds different in different musical environments. Our perception of a sound source is different in a cave or a concert hall or an apartment or in the woods. Instruments can sound different at night than during the day depending on where you are. Changes in temperature make it necessary to tune and take care of instruments.

Most instruments are affected by the environments they are in. Digital instruments are an exception.

What if environmental variations became factors in the sonic design of digital instruments?

Imagine a digital instrument with sonic design derived from local information:

- time of day (or day of month, month of year, or all of the above)

- temperature (around instrument, or in the town today, or the average of last week's temps in town)

- weather (would rain, sun, snow, wind, fog, etc make a difference?)

- place (GPS coordinate/city/state/country/continent?)

What physical form would an instrument like this take? What does an ever changing sonic identity mean for (probably) static physical identity? Would a strong physical identity be distracting or helpful for this kind of sonic identity?

I am intrigued with this idea of having an instrument that has an ever changing sonic identity. I laugh at the thought of someone asking "So... what does it sound like?" and me saying "I have no clue! We'll find out won't we!"

Yet, in order for an instrument like this to be successful there must be ways to control the instrument in at least slightly predictable ways. The sound and/or control could still be affected by the environment, but the performer must know what's going on. (at least a little bit)

I imagine performing with this instrument would be great fun in the setting of a worldwide tour. I have a lot more ideas about the implications of this kind of system, but I'll leave it here for now...

Most instruments are affected by the environments they are in. Digital instruments are an exception.

What if environmental variations became factors in the sonic design of digital instruments?

Imagine a digital instrument with sonic design derived from local information:

- time of day (or day of month, month of year, or all of the above)

- temperature (around instrument, or in the town today, or the average of last week's temps in town)

- weather (would rain, sun, snow, wind, fog, etc make a difference?)

- place (GPS coordinate/city/state/country/continent?)

What physical form would an instrument like this take? What does an ever changing sonic identity mean for (probably) static physical identity? Would a strong physical identity be distracting or helpful for this kind of sonic identity?

I am intrigued with this idea of having an instrument that has an ever changing sonic identity. I laugh at the thought of someone asking "So... what does it sound like?" and me saying "I have no clue! We'll find out won't we!"

Yet, in order for an instrument like this to be successful there must be ways to control the instrument in at least slightly predictable ways. The sound and/or control could still be affected by the environment, but the performer must know what's going on. (at least a little bit)

I imagine performing with this instrument would be great fun in the setting of a worldwide tour. I have a lot more ideas about the implications of this kind of system, but I'll leave it here for now...

Saturday, January 16, 2016

Initial Jitters

I have an admission to make; I find the process of thinking of novel interfaces to be very difficult. I'll design bespoke instruments all day long, but the interface with those instruments are in no way novel; if it isn't completely programmed or programmed in MIDI, than I'll use standard interfaces like drum pads or piano style keyboards, or sometimes going further back to simple analog knobs and switches if that is all the mechanism calls for. It's always been the aural and visual outcome rather than the feel of the input that I have concentrated on. That being said, I've never shied from challenge, so we sally forth.

In my initial thoughts on the problem, I started to recognize some basic needs which were key to me: should it be discrete verses continuous control? Can I have both? Will I be designing an interface and then finding a family of sounds that suited that interface, or is it the inverse; do I want a particular set of sounds and then I design the interface to suit them? Does it aid in musical execution and or lead to new creative avenues? And the most vexing to me of all because I have quite a bit of experience in music but almost none in design, what does it look like? How does it feel?

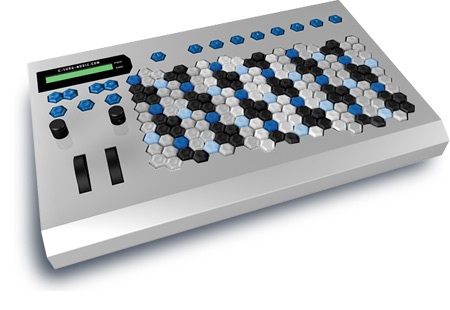

The difficulty in the question of discrete versus continuous control is this: when I design an array of buttons to give me the same amount of discrete pitch control that I would have in a traditional instrument there are two outcomes, and neither of them are satisfactory. The first outcome would be to just copy the fingering system from a traditional instrument, but then you have something derivative at best and a copy at worst; nothing novel there, might as well go with the original. The second option is to come up with a fingering system from first principles, a fingering system that was easy to use and at the same time allows access to multiple octaves and is flexible enough to suit virtuosic execution. I have seen several systems which were interesting and could support virtuosic playing before; for instance I have tinkered with the C-Thru Music controller,

which was an interesting and engaging interface, but as I was already experienced in both piano and saxophone, a MIDI keyboard or a MIDI wind controller suited me much better. Maybe I missed out on some new understanding of harmony using the C-thru, but I didn't have the time. That's the thing about a new discrete interface: it's a lot like the language Esperanto, well conceived, rationally constructed, made with all the best intentions, but it's nobody's native language and so remains of interest only to a small group of enthusiasts. Maybe that's why the C-thru has gone out of production.

A continuous controller seems a more productive route, yet it too can be musically limiting. In a gross simplification, a continuous controller is nothing but a variation on the mod or pitchbend wheel on a classic MIDI keyboard. There are strategies for getting around or compensating for this, but limitations remain. There are historical instruments with continuous aspects that can be played virtuosically; standard string instruments have no frets, the trombone has a slide. But once again you run the risk of making something derivative that would best be done with the original. It is imperative that some method of controlling an ADSR envelope be included in the design lest you sweep glissandi every time you change pitches or parameters.

There is of course a third way out of this dilemma, and that is using non-tonal or non-musical sounds only with your controller. While I am an enthusiast and practitioner of that aesthetic, it becomes problematic when combined with novel interfaces. Often the audience, and frequently even the musician, have a hard time decoding the relationship of the gesture on the interface with the audio result. In a live performance situation, too much novelty at once loses the musical link between what is happening on stage and it's place in historical and cultural context: we can take audio chaos in a live performance if it's apparent how the musician is doing it or we can take alien gestures on an interface as long as the gestures translate into meaningful audio effect, but both at the same time are just too much.

Which came first, the sound or the interface? This is a more philosophical question than a practical one. Of course, on any sort of musical instrument digital interface, you can assign whatever sound you want to whatever MIDI note or CC you assign to it, and the same holds true on any novel interface. That being said, and once again falling back on the metaphor of standard instruments, can you write a legitimate heave metal guitar line on a piano keyboard even with the top of the line software instruments, effects and amp modeling? Or is there something intrinsic about the way the intervals on the strings are laid out that would make playing the lines on the piano clunky where they flow effortlessly off the guitar?

My initial reaction as a musician is that, since ultimately the sound is the point of a musical endeavor, then the sound should come first. Once it's been decided musically what needs to be achieved, then you design the tool that allows you to most easily achieve it. But I wonder; through history, was every new instrument design based totally on the sound it would achieve? Could it have been that new sounds were made when the designer was just trying improve on the playability of an existing instrument, or just improve one particular aspect of an existing instrument? Was Cristofori intending to make a whole new timbre with his piano-forte, or just simply trying to get the damn harpsichord to have some dynamics and sustain? Did people say 'Nice trick Bart, but it doesn't really sound like a harpsichord anymore'?

So, while sound is obviously important, I'm tending towards interface first for a couple of reasons. One is that we have the freedom to assign any sound we want to it, so I'm sure there is something out there that can be made to suit. The second is that it's interesting to imagine the feel of a new instrument, how it hefts in your hand, how fast the action is, what motions are necessary and how their comfort (or lack thereof) contribute to the musical act and ultimately to the sound. This also leads to my next question from the introduction; how does it aid creativity? While I can and do think up new sounds and compositions quite comfortably on standard interfaces, maybe throwing something different in will lead to some new explorations, akin to a relatively tonal composer throwing some Serialism in to a transition just to shake things up.

I only know one Design dictum that I would hold to; Form and Function are one. As soon as you stray from that, superfluity begins to creep in. I was shocked the first time I found out that all the brilliant pillars and cornices of 18th century Italian architecture had nothing to do with the structure and were completely facade; it turned soaring heroic buildings into carnival displays. I am the opposite of Rococo (though I do have an occasional weakness for tasteful filigree). Beyond that, I haven't thought too much about the design of things. Either a thing works well or it doesn't, it's appearance is of little consequence. So when it came time to design something, I had to go fishing for inspiration.

I turns out this is harder than I thought. While the last century heralded a major explosion of interesting gizmos and clever solutions for modern living, currently most of those gizmo's utility has been usurped by the Swiss Army Knife of technological interaction, the touch screen. So many interactions have been brought under the sway of our thumbs that there are few examples of any sort of interface that doesn't include them. Even in all the major design blogs Ix/Ux are coding problems, not physical objects. The few places where I could find innovation in physical interactions involved jobs where people are still obliged to use their hands: tools and medical. Even in these cases, there aren't very many revolutionary advances, more tooling about the edges of proven designs: it's hard to improve on a drill motor.

So trapped between the ubiquitous history of musical instrument design on one side and the monolith of the touch screen on the other, I repeat my original concern, I find the process of thinking of novel interfaces to be difficult. It needs to be succinct, original, meaningful and done in a month or so. That being said, I've never shied from a challenge.

In my initial thoughts on the problem, I started to recognize some basic needs which were key to me: should it be discrete verses continuous control? Can I have both? Will I be designing an interface and then finding a family of sounds that suited that interface, or is it the inverse; do I want a particular set of sounds and then I design the interface to suit them? Does it aid in musical execution and or lead to new creative avenues? And the most vexing to me of all because I have quite a bit of experience in music but almost none in design, what does it look like? How does it feel?

The difficulty in the question of discrete versus continuous control is this: when I design an array of buttons to give me the same amount of discrete pitch control that I would have in a traditional instrument there are two outcomes, and neither of them are satisfactory. The first outcome would be to just copy the fingering system from a traditional instrument, but then you have something derivative at best and a copy at worst; nothing novel there, might as well go with the original. The second option is to come up with a fingering system from first principles, a fingering system that was easy to use and at the same time allows access to multiple octaves and is flexible enough to suit virtuosic execution. I have seen several systems which were interesting and could support virtuosic playing before; for instance I have tinkered with the C-Thru Music controller,

A continuous controller seems a more productive route, yet it too can be musically limiting. In a gross simplification, a continuous controller is nothing but a variation on the mod or pitchbend wheel on a classic MIDI keyboard. There are strategies for getting around or compensating for this, but limitations remain. There are historical instruments with continuous aspects that can be played virtuosically; standard string instruments have no frets, the trombone has a slide. But once again you run the risk of making something derivative that would best be done with the original. It is imperative that some method of controlling an ADSR envelope be included in the design lest you sweep glissandi every time you change pitches or parameters.

There is of course a third way out of this dilemma, and that is using non-tonal or non-musical sounds only with your controller. While I am an enthusiast and practitioner of that aesthetic, it becomes problematic when combined with novel interfaces. Often the audience, and frequently even the musician, have a hard time decoding the relationship of the gesture on the interface with the audio result. In a live performance situation, too much novelty at once loses the musical link between what is happening on stage and it's place in historical and cultural context: we can take audio chaos in a live performance if it's apparent how the musician is doing it or we can take alien gestures on an interface as long as the gestures translate into meaningful audio effect, but both at the same time are just too much.

Which came first, the sound or the interface? This is a more philosophical question than a practical one. Of course, on any sort of musical instrument digital interface, you can assign whatever sound you want to whatever MIDI note or CC you assign to it, and the same holds true on any novel interface. That being said, and once again falling back on the metaphor of standard instruments, can you write a legitimate heave metal guitar line on a piano keyboard even with the top of the line software instruments, effects and amp modeling? Or is there something intrinsic about the way the intervals on the strings are laid out that would make playing the lines on the piano clunky where they flow effortlessly off the guitar?

My initial reaction as a musician is that, since ultimately the sound is the point of a musical endeavor, then the sound should come first. Once it's been decided musically what needs to be achieved, then you design the tool that allows you to most easily achieve it. But I wonder; through history, was every new instrument design based totally on the sound it would achieve? Could it have been that new sounds were made when the designer was just trying improve on the playability of an existing instrument, or just improve one particular aspect of an existing instrument? Was Cristofori intending to make a whole new timbre with his piano-forte, or just simply trying to get the damn harpsichord to have some dynamics and sustain? Did people say 'Nice trick Bart, but it doesn't really sound like a harpsichord anymore'?

So, while sound is obviously important, I'm tending towards interface first for a couple of reasons. One is that we have the freedom to assign any sound we want to it, so I'm sure there is something out there that can be made to suit. The second is that it's interesting to imagine the feel of a new instrument, how it hefts in your hand, how fast the action is, what motions are necessary and how their comfort (or lack thereof) contribute to the musical act and ultimately to the sound. This also leads to my next question from the introduction; how does it aid creativity? While I can and do think up new sounds and compositions quite comfortably on standard interfaces, maybe throwing something different in will lead to some new explorations, akin to a relatively tonal composer throwing some Serialism in to a transition just to shake things up.

I only know one Design dictum that I would hold to; Form and Function are one. As soon as you stray from that, superfluity begins to creep in. I was shocked the first time I found out that all the brilliant pillars and cornices of 18th century Italian architecture had nothing to do with the structure and were completely facade; it turned soaring heroic buildings into carnival displays. I am the opposite of Rococo (though I do have an occasional weakness for tasteful filigree). Beyond that, I haven't thought too much about the design of things. Either a thing works well or it doesn't, it's appearance is of little consequence. So when it came time to design something, I had to go fishing for inspiration.

I turns out this is harder than I thought. While the last century heralded a major explosion of interesting gizmos and clever solutions for modern living, currently most of those gizmo's utility has been usurped by the Swiss Army Knife of technological interaction, the touch screen. So many interactions have been brought under the sway of our thumbs that there are few examples of any sort of interface that doesn't include them. Even in all the major design blogs Ix/Ux are coding problems, not physical objects. The few places where I could find innovation in physical interactions involved jobs where people are still obliged to use their hands: tools and medical. Even in these cases, there aren't very many revolutionary advances, more tooling about the edges of proven designs: it's hard to improve on a drill motor.

So trapped between the ubiquitous history of musical instrument design on one side and the monolith of the touch screen on the other, I repeat my original concern, I find the process of thinking of novel interfaces to be difficult. It needs to be succinct, original, meaningful and done in a month or so. That being said, I've never shied from a challenge.

I've been thinking about how to make an instrument respond to the performer. Though it could be said that a lot of DMIs are "dead", compared with physical, vibrating acoustic instruments, I think there is potential to use technology to imbed even more feedback/vibe/whatever into a performance device.

Looking through this paper on actuated instruments, I came across the Overtone Fiddle (a project I've previously heard of but had forgotten). This I think (regardless of the aesthetic of performance and design) is a good model for what I'm looking for!

Study No. 1 for Overtone Fiddle from Alexander Refsum Jensenius on Vimeo.

Looking through this paper on actuated instruments, I came across the Overtone Fiddle (a project I've previously heard of but had forgotten). This I think (regardless of the aesthetic of performance and design) is a good model for what I'm looking for!

Study No. 1 for Overtone Fiddle from Alexander Refsum Jensenius on Vimeo.

Friday, January 15, 2016

Music for Lamps and Surface Transducers

When brainstorming ideas for instruments, I thought back to a performance during the MATA festival in NYC that I saw last year, entitled Music for Lamps. Max Stein, Julian Stein, and Adam Basanta were the composers/engineers/performers of the piece, and you can read more about them and the project at their documentation hub here.

I remember that two things really struck me about the performance: 1) I loved the use of the "vintage" lamps. Like the Music for Lamps team, I am also interested in re-contextualizing everyday objects and imagining my own sound worlds in which to place them. Their fine control over dimming the lights, or abruptly turning them on and off created some exquisite moments of multimedia drama. 2) I was most impressed that sound was actually admitted from the lamps, in combination with a pair of overhead monitors. I spoke with the team briefly, afterwards and they explained that they attached surface transducers to the bottoms of the lamp so that they would resonate with whatever audio they sent through MaxMSP.

I love the idea of using surface transducers, and I think that will play a role in my projects for this semester. I think a lot of audiences find electronic music performances limiting when sound only comes from a pair of overhead stereo monitors. WhileMusic for Lamps probably won't work as a direct model for the digital musical instrument project (for a few reasons, e.g. there is no physical/immediate relationship the performer has to the system of lamps, rather it's mediated through MaxMSP), it served as a nice starting point for my thinking. Below you'll find a link to a full performance of Music for Lamps, the composition is pretty improvisatory so each performance will differ. I hope you enjoy!

I remember that two things really struck me about the performance: 1) I loved the use of the "vintage" lamps. Like the Music for Lamps team, I am also interested in re-contextualizing everyday objects and imagining my own sound worlds in which to place them. Their fine control over dimming the lights, or abruptly turning them on and off created some exquisite moments of multimedia drama. 2) I was most impressed that sound was actually admitted from the lamps, in combination with a pair of overhead monitors. I spoke with the team briefly, afterwards and they explained that they attached surface transducers to the bottoms of the lamp so that they would resonate with whatever audio they sent through MaxMSP.

I love the idea of using surface transducers, and I think that will play a role in my projects for this semester. I think a lot of audiences find electronic music performances limiting when sound only comes from a pair of overhead stereo monitors. WhileMusic for Lamps probably won't work as a direct model for the digital musical instrument project (for a few reasons, e.g. there is no physical/immediate relationship the performer has to the system of lamps, rather it's mediated through MaxMSP), it served as a nice starting point for my thinking. Below you'll find a link to a full performance of Music for Lamps, the composition is pretty improvisatory so each performance will differ. I hope you enjoy!

Thursday, January 14, 2016

Reflecting on the digital...

I've been doing a lot of reflecting recently on digital vs. analog spaces and how the digital online space in particular is changing our interactions with technology and also with each other. There's a constant search for the next new innovation or revolutionary piece of technology, and we've been reconditioned to crave immediacy and satisfaction. There are physical buttons you can order on Amazon that are linked to your credit card that will automatically reorder things from groceries to gatorade to diapers and toilet paper. With a simple press of a button, your order is placed and shipped to you within a couple of days. Social media has also conditioned us to crave that immediacy; many people receive the world's latest news through the online spaces they occupy; we habitually check our email and online profiles for updates, messages, likes, etc. The technological revolution has placed us in a position that no other generation has seen before; we are moving so rapidly that we can't seem to stop.

A couple of months ago, I ordered Douglas Coupland's new book, The Age of Earthquakes. Douglas Coupland is one of my favorite authors (and also Canadian!) and he often talks about how technology is changing (for lack of a better term) the human condition. Here are some of my favorite pages from the book (although the whole thing is amazing and I highly recommend reading it):

So where am I going with all this?

I think the development of music is reflecting this rapid unstoppable acceleration. We have apparently reached a point where physical acoustic instruments have largely been exhausted, so we've moved into the digital space, where it's faster, easier and more widely accessible to "create" music. Thanks to technology, you can synthesize apiano [insert other instrument here] track fairly quickly--much quicker than going through the motions of actually learning how to play the piano [other instrument].

Traditional classical instruments have evolved over hundreds and hundreds of years to reach where they are today. You can trace many instruments' lineages all the way through to the medieval ages. I think that the process of learning these instruments reflects that reiteration and refining; it takes years and years and years to master one of these more "traditional" instruments.

On the other hand, due to our obsession with pushing soundscapes and rapidly creating something NEW, new age instruments are lacking that same identity. Yes, we might put a lot of time (and thought and iteration) into creating a "new" instrument or interface to play music, whether that sound is created through digital or analog means. However, these new instruments or interfaces aren't receiving the same opportunity to evolve and grow and root themselves in a history, because of our fascination with innovation and rapidity. I mean, classical instruments went through the iterative design process, just drawn out over hundreds of years. So we're being called to design and create new instruments/interfaces, and yet you can see these new interfaces often being dropped or left behind after only a few months or a few years of development.

All of this ties into what Professor Gurevich has said about finding an identity for our proposed designs and finding an established aesthetic or tradition to root it into. How do my initial ideas relate to art movements or already existing instruments? What do I want the sonic/visual aesthetic of my instrument to be? Do my designs leave space for the instrument to grow and develop? Does it require the user to develop a certain kind of skill? How can I challenge myself to push back against this rapid acceleration and reflect that in my design?

A couple of months ago, I ordered Douglas Coupland's new book, The Age of Earthquakes. Douglas Coupland is one of my favorite authors (and also Canadian!) and he often talks about how technology is changing (for lack of a better term) the human condition. Here are some of my favorite pages from the book (although the whole thing is amazing and I highly recommend reading it):

Right: Proceleration (n.) The acceleration of acceleration.

Right (gray box): Fact: The internet makes you smarter and more impatient. It makes you reject slower processes invented in times of less technology: travel agencies; phone calls; reference libraries; nightclubs.

(I thought the right page was a big ironic)

So where am I going with all this?

I think the development of music is reflecting this rapid unstoppable acceleration. We have apparently reached a point where physical acoustic instruments have largely been exhausted, so we've moved into the digital space, where it's faster, easier and more widely accessible to "create" music. Thanks to technology, you can synthesize a

Traditional classical instruments have evolved over hundreds and hundreds of years to reach where they are today. You can trace many instruments' lineages all the way through to the medieval ages. I think that the process of learning these instruments reflects that reiteration and refining; it takes years and years and years to master one of these more "traditional" instruments.

On the other hand, due to our obsession with pushing soundscapes and rapidly creating something NEW, new age instruments are lacking that same identity. Yes, we might put a lot of time (and thought and iteration) into creating a "new" instrument or interface to play music, whether that sound is created through digital or analog means. However, these new instruments or interfaces aren't receiving the same opportunity to evolve and grow and root themselves in a history, because of our fascination with innovation and rapidity. I mean, classical instruments went through the iterative design process, just drawn out over hundreds of years. So we're being called to design and create new instruments/interfaces, and yet you can see these new interfaces often being dropped or left behind after only a few months or a few years of development.

All of this ties into what Professor Gurevich has said about finding an identity for our proposed designs and finding an established aesthetic or tradition to root it into. How do my initial ideas relate to art movements or already existing instruments? What do I want the sonic/visual aesthetic of my instrument to be? Do my designs leave space for the instrument to grow and develop? Does it require the user to develop a certain kind of skill? How can I challenge myself to push back against this rapid acceleration and reflect that in my design?

Wednesday, January 13, 2016

Imogen Heap + Ariana Grande + Mimu Gloves

From what I've gathered so far, there has definitely been a lot of discussion amongst the PAT department about Imogen Heap's Mimu gloves. They definitely seem to function more as a controller than instrument in my opinion, especially due to the fact that they can be applied across such a wide variety of instrument sounds. One thing that they do great, however, is create new ways to perform music and control effects.

While looking more into Imogen Heap's work I actually came across a video of pop musician Ariana Grande performing live with Mimi gloves. There are actually several videos of her doing this at different concerts, so she did it on at least one of her tours.

Here are a couple videos (I apologize in advance, as the quality is not great on all of them):

(In this second video, anything regarding the gloves is done after about 3:30)

In the second video, you can see there is actually in introduction by Imogen Heap about the gloves, which also features a video of Ariana doing a cover of an Imogen Heap early in her career. The video isn't perfect, but one thing I really take away from it is how the crowd reacts to the different ways the effects are controlled (even though the screams are very annoying). What I think is great about this is it shows young people reacting to new performance system that have been featured at NIME. This shows that these new systems can be accessible at a greater scale if we want them to be. I find this exciting, because so many great things are done in developing new interfaces and instruments but I feel that sometimes they don't get introduced to large enough audiences.

There is also a "tour diaries" video that shows Ariana Grande practicing with the gloves. In this video she clearly is having the gloves interface with a voicelive touch 2 vocal effects processor. I have used these processors many times, and based on what I know, the effect Grande is getting are coming from the voicelive. Basically, she just uses the gloves as a 3D control. Another thing I noticed is that her gestures are very limited, and I wonder whether she lacks skill or if there is just not that much to control. Here's the video:

While looking more into Imogen Heap's work I actually came across a video of pop musician Ariana Grande performing live with Mimi gloves. There are actually several videos of her doing this at different concerts, so she did it on at least one of her tours.

Here are a couple videos (I apologize in advance, as the quality is not great on all of them):

(In this second video, anything regarding the gloves is done after about 3:30)

In the second video, you can see there is actually in introduction by Imogen Heap about the gloves, which also features a video of Ariana doing a cover of an Imogen Heap early in her career. The video isn't perfect, but one thing I really take away from it is how the crowd reacts to the different ways the effects are controlled (even though the screams are very annoying). What I think is great about this is it shows young people reacting to new performance system that have been featured at NIME. This shows that these new systems can be accessible at a greater scale if we want them to be. I find this exciting, because so many great things are done in developing new interfaces and instruments but I feel that sometimes they don't get introduced to large enough audiences.

There is also a "tour diaries" video that shows Ariana Grande practicing with the gloves. In this video she clearly is having the gloves interface with a voicelive touch 2 vocal effects processor. I have used these processors many times, and based on what I know, the effect Grande is getting are coming from the voicelive. Basically, she just uses the gloves as a 3D control. Another thing I noticed is that her gestures are very limited, and I wonder whether she lacks skill or if there is just not that much to control. Here's the video:

Overall, I think it is great that a new interface like this is getting exposure in the realm of popular music. It is not nearly enough, but it is a good start. I think this also might motivate some people to consider how are instruments could be used on a larger stage. It would be really cool to keep seeing things like this show up in pop music, and even cooler to see it get better.

I would love to hear that thought of others regarding this. For or against, I think it is definitely something worth talking about.

Tuesday, January 12, 2016

Concept: Digital Hurdy Gurdy

I've been thinking for a while about the possibility of a digital hurdy gurdy, an instrument that generates sound from a spinning wheel (hand cranked) that excites three types of strings: melodic, drone, and percussive.

Here's my initial sketch

I decided to do some research on the hurdy gurdy and found that Derek Holzer has made an electronic one (though there's no computer or microcontroller inside). His electric hurdy gurdy is an offshoot from his Tonewheels project, and though it looks great I think there is plenty of room to expand on the concept. Details here: http://macumbista.net/?p=3020

His electric hurdy gurdy looks like this...

The design looks really solid and I love how it still looks (and essentially works like) a hurdy gurdy. If I decide to go through with this idea I would certainly reference Holzer's work.

Here's my initial sketch

I decided to do some research on the hurdy gurdy and found that Derek Holzer has made an electronic one (though there's no computer or microcontroller inside). His electric hurdy gurdy is an offshoot from his Tonewheels project, and though it looks great I think there is plenty of room to expand on the concept. Details here: http://macumbista.net/?p=3020

His electric hurdy gurdy looks like this...

The design looks really solid and I love how it still looks (and essentially works like) a hurdy gurdy. If I decide to go through with this idea I would certainly reference Holzer's work.

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)